In the hushed workshops of China’s ancient goldsmiths, a secret shimmered for centuries—the art of gold pressing and burnishing. Known today as Gu Fa Jin, this traditional technique transforms raw gold into luminous artifacts through meticulous hand-polishing, creating a patina that machines could never replicate. Or so it was believed. Now, a quiet revolution is unfolding as engineers and artisans collaborate to mechanize this thousand-year-old craft, not to replace human hands, but to preserve their legacy.

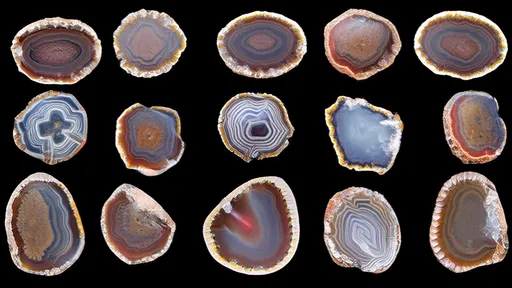

The process begins with reverence. Unlike industrial gold finishes that rely on chemical baths or electric polishing, Gu Fa Jin demands a slow, rhythmic pressing of gold sheets with agate or hematite tools. Each stroke aligns the metal’s crystalline structure, compressing imperfections into a mirror-like surface. "It’s like coaxing light from stone," says Master Li, a sixth-generation goldsmith in Beijing. "The gold remembers every touch." This organic luster—warmer and deeper than machine gloss—became a hallmark of imperial dynasties, adorning everything from hairpins to palace ornaments.

Yet time eroded the craft. By the 2000s, fewer than twenty artisans in China could perform true Gu Fa Jin. The labor—up to three weeks for a single bracelet—made it commercially untenable. Enter Dr. Zhou Wen of Tsinghua University, whose team spent a decade deconstructing the hand movements of masters into algorithmic precision. Their breakthrough came from an unexpected source: earthquake vibration dampers. "The human wrist absorbs irregularities during polishing," Zhou explains. "We mimicked this by developing a hydraulic arm with variable resistance, allowing the machine to ‘feel’ the gold’s texture."

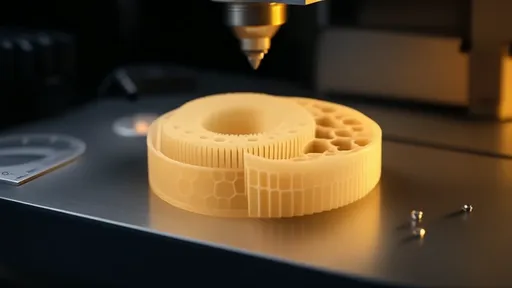

The resulting hybrid technology, patented in 2022 as Neo-Gu Fa, merges robotics with tradition. A robotic arm executes the primary pressing, but critical finishing stages still require a human’s nuanced pressure. Early tests showed promise—80% reduction in labor time while retaining 95% of the manual method’s visual depth. Luxury brands like Chow Tai Fook have already commissioned Neo-Gu Fa pieces, marketing them as "handmade by machine," a phrase that would’ve been paradoxical a decade ago.

Critics argue that mechanization dilutes Gu Fa Jin’s soul. "You cannot automate intention," insists Master Li, who refuses to use Neo-Gu Fa. Yet proponents highlight its preservation power. The technology archives exact pressure patterns of aging masters, creating a digital repository of techniques that might otherwise vanish. A 2023 exhibition in Shanghai displayed a Tang dynasty-inspired necklace—one side polished by a 78-year-old artisan, the other by Neo-Gu Fa. Most visitors couldn’t distinguish them.

Beyond jewelry, the implications ripple through heritage conservation. Similar projects now aim to mechanize cloisonné enameling and jade carving. As Dr. Zhou notes, "We’re not building robots to craft art. We’re building robots that learn art." The gold, it seems, will continue to remember—even if the hands that shape it are sometimes made of steel.

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025